Kim Oliveros

Neil de la Cruz

Rocelie Delfin

Kim Oliveros

Neil de la Cruz

Rocelie Delfin

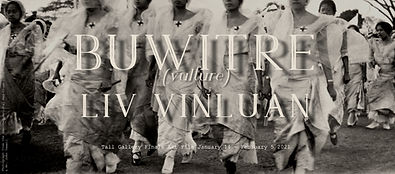

LIV VINLUAN

Buwitre (Vulture)

Omens in Time

"I think I may have entitled this show Buwitre (Vulture) because maybe, this is what is left and picked off after a pandemic – some hefty personal introspection and many, many lessons learned. I am just any woman trying to maneuver my way through a hedge maze of house chores, being a wife, a daughter, a sister, making a living, making sense of a pandemic, and being a painter." Wrote artist Liv Vinluan as she communicated the essence of her current exhibition. The vulture holds a venerable symbol of "purification, compassion, and maternity" in ancient Egypt. The bird of prey performed the necessary service of cleansing the world of stench and rottenness when it was taboo to touch dead bodies. This seemingly morose association to the displayed sentimental works brings the discomfort that is requisite for the idea to permeate through our consciousness.

The work Burning of Manila captures much of our recent days – being witnesses to tragedies as they unfold. The artist asks "What does it mean to make and engage in art in the time of a raging pandemic?" Beautifully merging her concerns, Manila is Burning II shows two young artists paint the inferno that is Manila while standing on a massive floating battleship. In her representations, she brings to the fore trivial inquiries without oversimplification, but an attempt to untangle the complex baggage of being both a Filipino and an artist. She is heavily influenced by the history of art and nation, visibly shown in her use of the glazing technique done by old masters while investigating the cyclicality of our country's narratives. Layering paint and chronicles from dull, dry shades of gray with horror stories on land and sky. The process has a waiting period that creates a push and pull dynamic allowing for space and time for contemplation. Another day, another battle.

It is often imagined that artists live in recluse, inside their creative worlds. In Liv Vinluan's body of work, the contextual plane is rendered more evidently to accommodate an understanding of the interdependence of personal and social conditions in artistic production. The works of art are positioned in intertwined epochs, relating to the artistic vision that is not separate from existing. From where the artist stands, it is clear that as the vulture consumes death, rebirth is not far from the horizon. (Con Cabrera)

BEMBOL DELA CRUZ

And the Rest Was History

In And the Rest Was History, Bembol Oligario Dela Cruz delves into the secret—and often pernicious— history of ordinary objects, as exemplified by the iconic forms of the manual typewriter and the Volkswagen Beetle. Though they look innocuous, some objects trace their roots in the dark chapters of the human story, such as fascism. The Beetle, for instance, replicated by Dela Cruz in life-size scale, was the brainchild of the Nazi Germany’s leader, Adolf Hitler, who commanded Ferdinand Porsche to design a car that was as affordable as the then-ubiquitous motorcycle and would ply the network of newly built roads under the Reichstag. Though production has been discontinued in 2003, the Beetle remains a beloved icon by automobile connoisseurs, prized for its impeccably modern silhouette and efficient engine. In the painting, the car is disemboweled of any discernible machinery and wheels, presenting the husk of what was considered an automotive achievement, as if hunted by the burden of its undeniable past. Though defunct, these inventions have informed succeeding innovations (the laptop and the driverless car), part of the grand scale in the evolution of inanimate objects. Placed within the ambit of the viewer’s attention, these paintings are part visual record of obsolete technologies and part illumination of their history—the medium being the message.

-Carlomar Arcangel Daoana

LYRA GARCELLANO

Guests

Draped in the Stars and Stripes, the man brandishing the walis tambo in the Capitol Hill riot is reportedly Ilocano. Although a minority in a predictably white crowd, he is far from the only person of color in the siege. Amidst the Confederate, Tea Party and Neo-Nazi flags associated with the far right, there were a few colored faces carrying their own symbols: the man from Kochi with an Indian flag, several Asians from South Vietnam, Japan and South Korea carrying their own ensigns. Sure, there were other flags: Australia, Canada, and Israel, and even LGBTQ+. Some of them were refugees, some of them guests. A good guest helps their host.

As a part of the world slowed down to stare at the latest American car crash, it was much harder to look away when you noticed the minorities in the details. It's not just schadenfreude when you catch glimpses of yourself.

When Filipino artists Jose Honorato Lozano, Damian Domingo and Justiniano Asuncion were developing the style of watercolor illustration known as Tipos del Pais in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were not just creating an art of Filipiniana representation, but rather mastering a manifestation of the much older art of catering to expectations. An auto-exoticization. As the colonial powers changed from Spanish to American to neoliberal economics, the market remained essentially the same. Skin tone still meant social standing and modes of dress still signified status.

The consumer is not seen. In color, the consumer presumably has lighter skin, if not in complexion then in outlook. The consumer is a connoisseur of the exotic, of folk art, yet never really of the folk depicted. The consumer buys what is expected. What is expected is the retention of a status quo.

Tributes for kingdoms, keepsakes for tourists. Sometimes it's just a matter of scale. Decolonial processes have equipped you with the tools to identify these: the consumer from the consumed, the proletariat from the capitalist, the guest from the host. But they are tools for identification, not emancipation. The borders and binaries are in a constant state of collapse.

Yet a form of feudalism persists, no longer of land and bodies, but of language and minds. Trading dress and lightening the shade of a Filipino or a global social experience does not really change thinking. A terrorist could be a freedom fighter. A guest could be a migrant worker -- no matter how many Star-Spangled Banners, no matter how perfect the American accent.

As soon as you retake the power, another form of power is co-opted. When you center blackness and the experience of subjugated minorities, you tip the balance and something spills over: dark stains on white Manila paper. Reality becomes stranger -- or you become more aware of its absurdity. A brown Ilocano is not expected in a white bigot rally. Yet there he was. All dressed-up. Tipos del Pais. A good guest helps their host. (DC Dulay)

CLAIRELYNN UY

Twisting my Melons

It's often repeated that we, Filipinos, usually adapt to survive. For most of 2020, everyone had to figure out how to deal with all the disruptions and problems that the covid crisis brought to the fore.

There was the ayuda, the jumanji, and the mañanita. With each passing month, it seems like situation here finds new ways to disarm us.

But I think there's something very positive in that, despite all that happened, we look at all the things confusing us and find some way to make it funnier, into something we can enjoy and joke with each other.

The show is a storytelling of the different ways we've learned to channel our energies, of how we can find the comedic within the tragic, of how we route current events into a different dimension of 'hah, anong nangyari?'.

JOEY DE LEON

In the House! (Art... Work from Home)

Joey de Leon, more known as a comedian and a mainstay host of the longest variety show in the Philippines, Eat Bulaga!, displays his mettle in the field of visual arts in his solo exhibition, In the House (Art...Work From Home). As early as the 1980s, de Leon has already been showing his works and collaborating with visual artists, some of whom would eventually become masters and National Artists. This current presentation at Finale Art File reunites de Leon with his first love and joy: of making marks and applying colors on canvas.

These paintings of varying sizes were accomplished during quarantine, which is still in placenationally. With the time and space to sit down and paint, de Leon’s initial forays were attempts to make sense of the current reality of the pandemic. For instance, in “No Mas Face!,” de Leon explores and makes fun of the ubiquity of face masks, with “face” transformed into the visual pun of “peace” and “fish.” Taking into account that “mas” is the Spanish word for “more,” the title means, “no more face,” which directly alludes to how the masks have totally obliterated the face of wearer.

Words, both as titles and typographical presence in the paintings, are important elements in the works of de Leon. In some cases, the words lead to paintings, as de Leon gives puns, idiomatic expressions, and Biblical verses a visual interpretation. For instance, in “Uni-corn,” the horn of the mythical creature is transformed into maize. In “And Blessed is the Fruit,” a still life turns into a devotional painting, with the fruits forming the shape of a man in contemplative prayer, his avocadoseed-eyes trained on a full moon.

What is sustained as some kind of a theme in this exhibition is how numbers are arranged into scenes of Biblical import such as the Nativity and Crucifixion, putting a new twist on numbers as being “figures.” Working with numbers, de Leon states, gives him the constraint in order to imaginatively come up with his cryptic compositions. The order the universe as expressed by numbers and the magic of divinity through the religious themes fuse in these works.

The lockdown, in providing de Leon the space to touch brush on canvas, has become an opportunity for the artist to explore the flexibility of the acrylic medium as well as new themes. That these works are animated by a sense of play and exuberance is evident, injecting a sense of levity to a form of art notable for its high seriousness. The paintings of de Leon, in their refusal to play by the rules and subscribe to conventional tropes, are inflected with a crackling energy, redolent with visual puns, surprising juxtapositions, and the transformation of numbers as image.

-Carlomar Arcangel Daoana

VAN TUICO

Loaded with Concrete

Loaded with Concrete presents recent works by Van Tuico. Known for his paintings created with acrylic paint and industrial materials, here the artist propels his creative production further by generating deception in perception. The displayed collection of objects intends to translate construction materials into a sort of concrete language built by loading additional weight and layers of significance. The aim was to innovate and enact an adaptation to the antiquated yet tested. He wanted to optimize innate representations of the familiar within a fairly unfamiliar terrain.

Tuico challenges the words abstract and concrete in this exhibition. Much like the double entendre literary device that has multiple senses and interpretations, he presents different ways of understanding. In his attempts to turn concrete as a language system made visible by the abstract form, movement is both physical and philosophical. Concrete referents are shaped even with spatial and imaginative constraints. To accomplish this exercise, the artist brought together different materials to blend what is common to uncommon grounds. In exaggerating and distorting his weathered materials while referring to Brutalism, it was beneficial to familiarize himself with the form, purpose, strength, and capability of both style and matter.

The artist's body of work is visible gathering performed through his art-making wherein the spiritual reckons up. In the acts of summoning and assembly, the bigger picture of life is rendered.

GROUP SHOW

Alternating Atmosphere

Joey Cobcobo

Dex Fernandez

Mark Andy Garcia

Eugene Jarque

Doktor Karayom

Lynyrd Paras

Mac Valdezco

To alternate is to take turns. In our current pluralistic environment, we have developed a conditioning that we can have manageable expectations, but at the same, accept that there is a great deal of uncertainty in living the art(ist) life. This exhibition brings together alumni from the Technological University of the Philippines (TUP), who were also recipients of the coveted Cultural Center of the Philippines Thirteen Artists Awards, to map out testaments to the possibility of sustained creative growth while being supportive to your peers. An apt timing as the CCP recently closed the call for nominations for the triennial awards, these seven contemporary artists remind us of the diversity of the types of art and artists the university in dense Manila has been consistently producing. When Roberto Chabet wrote the curatorial guide for the awards, it was emphasized that the awardees should be "a new generation of artists that promise to dominate Philippine art," who "constantly restructure, restrengthen and renew artmaking and art thinking.”

taas | baba

In a 2020 news feature titled "The T.U.P. Artist has finally arrived", struggle in art life was central to the candid interview, revealing a lot about the group's value systems. Most, if not all, artists here come from working-class families and had to grapple with economic limitations to live and produce art. The comfort and liberty they now experience are products of rising above obstacles as they were able to transform these hardships into fuel in artistic conceptualization and creation. This exhibition then does not aim to manifest a specific statement. But it is a display, a demonstration, of camaraderie that is fostered through time and has embedded amongst them mutual respect.

liwanag | dilim

When asked how TUP shaped the exhibiting artists' competitive nature and unconventional practices, they all pointed at Eugene Jarque, who was a former teacher to most of them. They attest to the inspiration and influence that was dynamic through its openness, honesty, and challenging yet nurturing manner. Of course, the existence of art competitions that was crucial to their production because of the prizes and eventual validations in the artworld was also acknowledged. Inevitably, Jarque attributes this encouraging and alternative thinking to LirioSalvador, the TUP alumnus who was instrumental in lifting the university into the art spotlight. Salvador brought the experimental ethos that was appreciated and embraced by many, especially by the artists in this group. The medley of styles and approaches displayed is proof of this radical spirit.

init | lamig

Jarque's and Valdezco's persistent experimentation with materials, Cobcobo's methods of marking, Paras's and Garcia's evaluation of identity and the self, Fernandez's and Trinidad's fictional worlds – these concerns and modes of making are all by-products of self-development forged in fire that is constant in the midst of the realities in life. Awards and recognitions are but part of the chains of validation in the ecosystem of art. They may inspire or stimulate artists to do better and be better. Ultimately though, it is the sense of belonging, and to be able to cultivate one's creative life to take part and impart in this milieu is central. (Con Cabrera)

LING QUISUMBING

Debris

This is the debris of labor.

Christina Quisumbing Ramilo brings focus to the invisible labor behind works of art by using accumulated discards from studios, workshops and the supply stores that she frequents. She brings into plain sight the hours of toil and chaotic reality that come with artists’ noble role in society to enlighten, critique and record. Despite their unique position in shaping culture and politics, most artists live within a precarious economic situation. Unlike other stable wage earners, artistic labor has no fixed value.

With her distinct purist approach, Ramilo handles the detritus with minimal intervention to the conditions they were found in. Contrary to the worthless nature of discards, recycling them poses a more difficult challenge than buying new materials. Their inherent limitations in size, shape, color and quantity are a struggle to assemble, like multiple complex puzzles. These large-scale compositions may appear seemingly random but are the product of minutely deliberate intentions. Grid-like patterns draw our attention to richly textured patina. Hence she treats the material with utmost respect, exploring the relationship between chance and order, error and possibility, revealing the intrinsic beauty in what has already been overlooked or cast away.

Throughout history, the use of humble materials for art has often been a means to dissolve the borders between art and life. Ramilo brings this principle to a more personal level by selecting discards from artist friends: their used paint rags, brushes and sandpaper, and from her own discards, including hundreds of receipts that highlight the endless expenses an artist must be able to cover in order to survive without a steady source of income. Receipts form a portrait of the consumer, and in this case a vast majority of them, apart from living expenses, are from hardware stores—the main source of material for an artist who primarily makes assemblage.

Each discarded item contains clues of the original owner’s purpose. Some sandpaper pieces are more thoroughly worn out than others, with tell-tell signs of paint colors, surfaces and edges they had been used on. Painters’ rags reveal to us their preferred color palettes. Scribbles to test inks at supply stores show us what type of pens strangers have considered purchasing for their needs. These are marks of history embedded into the materials and become part of their character, such that time itself is a collaborator in the finished product.

Ramilo spent many years working jobs that involved art-related labor, including supervising at the painting department of a bronze foundry, part-timing as a gallery art handler, working at an art supply store, teaching art at university and working at the Frick Art Reference Library. Her consciousness on labor intensified when she built her own house as a monumental assemblage of recycled architectural fragments. Approaching her 60th year, a diminishing capacity for manual labor has led her to adapt the scale of her works by making smaller objects installed into groupings that form larger assemblages. As one of the few female artists in the Philippines who constructs in massive scale, she challenges expectations of the type of labor associated with women.

The Tall Gallery has allowed Ramilo the most expansive presentation thus far reflective of her studio practice: often working simultaneously on pieces whose parts have been collected over decades. Inside the white cube, we are invited to see what she sees; the faintest details become more pronounced when taken outside of their daily setting. We are posed with notions of propriety and value and question assumptions surrounding labor. The dignity of labor as a source of inspiration and investigation is given center stage with the overwhelming significance of its debris. (Stephanie Frondoso)

TIFFANY LAFUENTE

The Naughty Grail

In the exhibition, Naughty Grail, Tiffany Lafuente explores the dark core of the human psyche that underlies the society where we inhabit.

The artist puckishly inserts visual cues that evoke associations between historical and contemporary moments in order to foreground the age-long entanglements of art, life and capital. Rigorous portrayals of the interior, steady frontal compositions and movements created by light and shadow recall the traditions of portrait paintings, particularly of 16th to 18th century Europe, during which the new wealthy emerged from the worldwide mercantile system established along with the colonial aggression. Portrait painting was not just a way for the new patrons of art to record their appearances, but also to visualize, exhibit and assert their taste, wealth, status and power.

Lafuente's paintings presented in the exhibition are the portraits of the players of hostile expansion of capitalism that alienate, exploit, destroy and eventually lead into self-destruction. Donning business attire, the anonymous entrepreneurs are self-involved without the awareness of the mischiefs done to them by the ghostly apparitions of the sitters in the classical portraits that they own. The women in the paintings open their mouths big and round mimicking the vinyl sex doll. The nude male model emerges from the painting and messes up with the businessman in his nap. Enlivened by the spirit of the king in the painting, the knight's sword cuts in the game of power abuse.

Lafuente's work pushes further the critique of global capitalism, digs deeper and exposes our voyeuristic curiosity triggered by the images of people immersed in sexual fantasies. It is a reminder that we are already grained in the narratives produced and manipulated by the ideologies of capitalist economic systems. The dense impasto robustly applied onto the canvas vandalizes the image as if to reflect the constant attempt striving to oppose, negotiate and rework on the dominant structures. (Mayumi Hirano)

MIGUEL PUYAT

Same Shapes, Different Each Time

Ornette Coleman’s celebrated 1959 album, “The Shape of Jazz to Come”, prompts Miguel Puyat’s first solo exhibition. Here, the artist likens the process of his art-making to Coleman’s improvisation and unique approach to arrangement where every composition contains brief thematic statements and then, several minutes of extemporization. Similar to jazz, Puyat’s works are configurations that require interaction and collaboration from both viewer and receiver. The production of the work extends beyond the artist’s studio and allows public participation to manipulate and transform the object, far exceeding the artist’s initial plan.

Drawn by a statement where Coleman had once said, “jazz is the only music in which the same note can be played night after night, but differently each time”, Puyat replicated the same sensibilities in producing objects that use basic patterns, forms, and shapes but with the ability to construct different images as one desires. Similarly, free jazz is recognized in its propensity to be controlled through the performer’s actual feelings, emotions, and interactions with his environment releasing the art from any rules and canonical adherence. Hence, Puyat’s realization of the work becomes an exercise in playing and problem-solving; what and how should one make art? What is there to come? Perhaps, the response lies in the way Puyat generously designs his works: removing the boundary between artist and audience or accepting their interchangeable roles. In essence, jazz is absorbed in the same invisible contract of radically presenting something that wrenches the heart and punches the gut.

Miguel Puyat (b. 1993, Philippines) is an interdisciplinary artist whose practice embodies the principal focus of Process Art, where the actions and steps in art production are far more important than the form of the object. Puyat explores a range of narratives that hint at existentialism, nostalgia, and subcultures as he examines the alteration and manipulation of found materials such as existing objects, sound, video, and images. (Gwen Bautista)

AYKA GO

some things we call home

The recreation of sensuous surface has long been the allure and conceit of painting. In some things we call home, Go continues her long-standing interest with paper and the interplay of the two-dimensional vis-a-vis space and mass. In these paintings, fragmented scraps-- with their splattering of pattern and texture-- bulge with volume and heft. Folds and tears signal depth and form. An unseen object serves as scaffolding, akin to bones and organs stretching out papery skin. The experiential hints at an interiority.

Inside these packages, Go makes use of toys, reminiscent of her own family and childhood, as references. But in a reversal of gift-giving celebrations where newly bought things emerge from shiny gift wrappers, here, the objects gathered are burdened with memory. Enclosed in seemingly brittle and aged paper, they evoke nostalgic longing. And occluded from view, we regard them in a strange light. In effect the artist is staging a re-encounter, as if from within the creases a toy can tumble out reborn. As if she can offer these old things anew.

Partly a response to the vicissitudes of current times, partly a remembering, her works signal towards the accretion of loss and the rituals of coping. And perhaps, it also gestures to a certain promise. That soon enough, through disparate shapes and ways, the weight of the past can also coalesce into forms of gratitude.

- JC Rosette

LILIA LAO

endearment

Through her persistent dedication to art making, Lilia Lao has gently captured the texture and atmosphere that surround her everyday life. Her affectionate attention finds irreplaceable and unrepeatable expressions in the mundane.

Lao's long-awaited solo exhibition comprises a selection of the paintings made between 2012 and 2021. As the artist describes the subjects in the exhibition: "the objects and environments that inspire me all over again," the assembly of the works here present a series of renewed discoveries through the artist's experimentation and self-reflection over the passage of time.

The word, inspire has its root in the Latin inspirare, meaning to breathe. The brush moves as the artist breathes, grasping the presence of air circulating in-between her and her subjects. In a tranquil encounter with her subject, the artist receives energy to inhale and exhale. Lao's artworks remind us of the preciousness of each breath that enables our lives.

The word spirit stems from the same root word as inspire. Breathing enlivens the spirit within us. Listening to the natural rhythm of breathing is an exercise to reconnect with our self and with the world around us. It is a practice to find eternity in each moment. In this exhibition, Lao invites us to immerse ourselves in the meditative process of her art making, where she recognizes preciousness and beauty right in front of her. We are reminded that the spiritual dimension of art and life does not lie anywhere afar but here within us.

Mayumi Hirano

KIM OLIVEROS

New Ending Old Story

The artist recounts awaking to the sound of the sewing machine as a child;

a mechanism which served to be his alarm clock on a school day.

His playground resembling a dance between order and chaos,

Oliveros vividly describes exploring his mother’s factory workshop:

a tight turvy occupied by mounds of fabric thickened with the agitation of a buzzing noise;

the kernel within this frenzy being the consistency of pattern—

a tranquility which seems to have hemmed the artist’s attitudes.

As children fear the unknown, routines protect their sense of security.

Attaining a sense of equilibrium through the sterile progressions of his process,

Oliveros terms his painting procedure a concrete plan.

While others seem to reject the banality of manual labor,

Oliveros embraces every step of craftwork with an exhaustive thoroughness,

declining all supposed benefits of delegation;

The artist needing to do all things by himself, for himself.

In “New Ending Old Story,” the painter counters all traces of disruption by

stitching refuse from his former shows: fringed imagery woven as pattern—

a stillness calming the variabilities of our present disarray.

(Words by Dani Valenzuela)

NEIL DELA CRUZ

Boundless

In the Digital/Analog world.

These images? Yeah, The artworks.

What’s up with that.

It’s up to you, or it is up to me.

That painting. Is it allowed to be by itself?

Can be.

An infinity pool of color alienated strokes?

Can be.

Lines of force?

Can be.

Or they’re just a matter-of-factness.

“A compilation of the physical reality”?

Sure.

But then again, it is a sensation of real presence and real action.

Or just another unexpected cure!

Still.

It’s up to you, or it is up to me.

These boundlessness,

The endlessness,

The self-sufficient dynamism.

It’s allowed to be by itself. That painting.

Oh, the paintings.

Let them be,

Can be?

ROCELIE V. DELFIN

Bato-Bato sa Langit

Rocelie Delfin’s drawing series of unusual rocks has been an ongoing endeavor for many years. This exhibition encompasses the progress of their evolution, beginning with a focal point on single rocks. Later her unique drawing technique is translated to the shadows of individual trees cast over rocks. Recently she depicts them as part of larger, more complex compositions that make up forests and bird habitats.

The rocks are based on a collection of smooth grey lined rocks from Taiwan. Delfin applies hundreds of miniscule lines to mimic the tiny markings on the rocks’ surfaces. Through the use of a thicker ink pen, the lines appear softer and more feathery, creating a visual tension that is both meditative and mesmerizing.

For the succeeding series, Delfin abandons the use of references and draws entirely from imagination and memory. Twelve small drawings are of fantastical trees whose shadows are cast over rocks. The roots, sometimes absent, are smaller than reality—her direct way of portraying that above ground, only the upper part of a tree’s roots are visible and in some cases are completely hidden underneath the soil. In the larger drawings, the rocks belong to scenes that include birds, plants and houses, each subject scaled with surreal perspective and proportion. The single largest drawing, titled “Buhay na Bato”, shows plants growing on rocks. The term “living rock” refers to rocks where plants have taken root from soil sediments caught in their rough surfaces, the rocks thus becoming a microcosmos of different organisms.

These are curious drawings, with sincerity and spontaneity ruling over other concerns. The forests recall ones we see in storybook myths and fables rather than the truly menacing jungles of our world. Yet Delfin captures their wildness, densely packed with obsessive detail. Beneath the enchantment, these drawings hold mysteries that leave us pondering time and again. (Stephanie Frondoso)

LYNYRD PARAS

Atake sa Ulo

Para sa eksibisyon ni Lynyrd Paras

Namumukadkad daw ang kaluluwa sa ulo

Kung saan lahat ng mga pandama ay hagip

Ngunit hindi pa rin matunton ang ako

Kahit sa pinakamalalim na panaginip.

Ipinihit na ang sarili sa malamlam na araw.

Anino pa rin ang sadyang nasisilip.

Tinupad ang pagbagtas sa daang mapanglaw.

Mga multo pa rin ang sa utak sumisirit.

Paano ba lagyan ng tanikala ng isip

Para makapaglayag sa daluyong ng alon?

Bumukas ang mga mata ng dagat na naiidlip.

Inundayan ng kidlat ang isla nang poon.

Dama ko ang hangganan ng balat.

Nagnanaknak ang durog na pintura sa kanbas.

Bakit hindi pa tumikom kung ano ang mulat

At para sa ibayo ako ay makaalpas?

Kakalabitin na lang ba ang gatilyo sa sintido?

Yayanigin ng apoy ang utak at dugo.

Baka sa matinding pagkawarak ng bungo

Doon magkakapugad ang sarili sa basyo.

- Carlomar A. Daoana

JEMIMA YABES

Once Alive

A year into this crisis, there is nothing else that we need more than rest. But with lives at risk and tomorrows in peril, to rest has become an invitation for guilt and an admission of defeat - so we begin to mistake chaos for calm because all our life we lived in storms.

Such are the contradictions and the elusiveness of rest that Jemima Yabes confronts in Once Alive. Taking off from her quest for peace after more than a year of quarantine turmoil, Yabes seeks calm through images of seemingly lifeless forms. Yet in this process, she discovers something more: to be still is not to resign possibility, but to persist. After all, contradictions abound in today's unending unrest: life is at a full stop, but it is also on the verge of collapse such that chaos and calm become entangled and we no longer recognize their singular forms. So Yabes comes up with a hybridized state: the state of being once alive - where movement resists stillness, and life endures despite death.

In this pursuit, Yabes mobilizes stillness to bring forward the movement deceptively inherent in these inanimate images. Do Dogs Dream? depicts her fascination with the tranquility of sleep that betrays the flurry in one’s dreams. The conflation of life and death is also demonstrated in her emblematic meat paintings, where she puts forward the irony of meat acquiring its nutritional - and, by extension, life-giving - capacities only through its slaughter. Her intentions behind her reproductions of the bird’s nest and tea leaves using frayed paper transfer also operate on a similar line: to demolish only to rebuild, it is a ruin that reconstructed nature - nothing less than life.

In one aspect of the term, these objects were once alive - once living, once lively, once devoid of destruction. But as Yabes contends, what was once alive may still find life. Amid ruin, madness, or catastrophe, one may still triumph and regain lost life. This conflation of life and death, victory and loss, is indicative of the contradictions of our times: on the one hand, the world is at a standstill; on the other hand, it is falling apart. In any case, the possibility of life and victory remains. Thus, to rest, to halt, and even to die, is not an ultimatum in life. Because life can still be reclaimed even after pause or defeat. To be once alive, then, is for hope to persevere. (Chesca Santiago)

Night Mirrors

MARIANO CHING x YASMIN SISON

EDMUNDO FERNANDEZ

Drawings

From Residencies in Japan and France

This is a homecoming. Bro. Edmundo Fernandez stayed at the Vermont Studio Center in 2010 for an artist residency and shared his works through the gallery in an exhibition titled Suspended in 2011. A decade later, this same space presents the artist's drawings done in his artist residencies in Japan and France in 2019. Bro. Dodo is known to most as a Lasallian brother and the president of two La Salle schools – a religious and a leader who lives a life of service. "My life is a bit dichotomized." He said as he began to talk about his college life and finishing a degree in Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines. Manifestly, choosing to be a brother directed him to a different path. Despite the demands of his work in the institutions he belongs to, he is aware that his life journey is dedicated to bridging the seemingly disparate dispositions of art and administration. He walked the Camino in Spain by himself, which was 800 kilometers for 38 days, from town to town. He remembers this as a wonderful experience – it was life-giving. In a sense, this is similar to his immersions in artist residencies. Bro. Dodo feels that he only has time to make art when in recluse in the studio, because art-making consumes him. It's a complex mindset that takes up every ounce of physical, psychological, and emotional energy of his body. Such a necessary condition in art production makes the artworks displayed rather special.

While in Onishi - Contemplating mortality

The works made in Shiro Oni Studio Gunma, Japan depicts the artist's fascination and meditation on the transience of life and his abhorrence of war. He's so enchanted by the fact that there are myriad ways of expressing the value of existence, or even when death comes upon us. He was so moved by the mental picture of persons jumping from the Twin Towers during the September 11 attack in the US. The very intense process of drawing images of Holocaust victims perhaps reflects the minor vocation crisis Bro. Dodo went through during this time. "It might have also prefigured all the death in the pandemic." He said. In the very serene act of composing small lines to lend light and shadow, it was like hearing the artist think. All this thinking enters his spirituality.

While in Caylus - Freedom in his terms

At one point though, Bro. Dodo grew exhausted from drawing the dead human bodies. A week after staying in Japan, he traveled for the artist in residence program of DRAWinternational center in France. During this respite, the first week and a half were spent inking a meticulously shaded nautilus. The spiral shell drawing shows a very controlled technique. His lines and tonal gradation were exact. However, the encouragement from the artist's mentor to loosen up resulted in sketching of dead flies. His mentor liked these fly drawings because they were less rigid. Even though they seem unconstrained, the pre-production still consisted of detailed research on the anatomy of the insect. Nonetheless, the artist enjoyed the fact that he was illustrating lifeless flies in a small town far from work demands.

"Just as the bird sings or the butterfly soars, because it is his natural characteristic, so the artist works..." wrote Alma Gluck.

This brother is an artist. Bro. Dodo, in realizing the two lives of art and administration still both belong to his person, is able to summon the necessary skills and creativity as he performs his duty as a religious and leader. This sense of freedom propels his ideas to execution, innovating, and thinking beyond. There is a great deal of courage in imagining futures and reconstruction of values in his context. His drawings are proof of this. He intentionally creates the feeling of flight or suspension or the absence of an environment to focus on single images – with all its intricacies yet a refusal of closure. Sincerely because the artist always wants to come home to art. (Con Cabrera)

JOJO SERRANO

Aquatico

Jojo Serrano's art-making begins with diligently creating collages by culling and cutting out images, which he then transfers onto a canvas using paintbrushes. As the artist describes the process as "faithful recreation," Serrano intimately studies and reproduces the original images by exploring the effects of photographic images.

The density of his handwork dismembers the narratives embedded in overflowing media images and slows down the production, circulation, and consumption of visual information in contemporary life. It is a solitary practice, a quiet attempt to unravel the perception of the world coordinated by modern technologies.

The ceaseless advancement of modern technology continues to deepen the discourse of dichotomy that disconnects our life from nature and legitimizes the abuse of power of humans over the natural environment. Encountering Serrano's new series of work composed of octopus, jellyfish, shells, creatures from the sea, I am reminded of the intricate networks of life existing at a depth of the ocean. Within the ecosystems, every life has an equal significance. Even death has a meaning.

At Earth's deep point, humans are extremely vulnerable as we lose the ability to breathe while the millions of creatures maintain their life balance. The chain of life below water sustains itself as the complex circulation of the subtle signs of nature that are indiscernible to human eyes. The intelligence and powers of the sea/amphibian creatures betray our knowledge and expectations. Close attention to the life-and-death mechanism of each organism reveals the limit of our worldview constructed by the binary rhetoric. Merging individual elements, sinuous, undulating, flowing movements in Serrano's works navigate the viewer's sight fluidly across the canvas, inviting to imagine breathing synchronously with the sea creatures and to recognize oneself belonging deep into the natural environment.

Mayumi Hirano

MIGUEL LORENZO UY

Out-of-body simulations

Miguel Lorenzo Uy presents a new body of work in his fourth solo exhibition. Uy’s current interest stems from speculations on how technological advancements have proven to radically alter the meaning of our memory and identity. Consequently, political and economic affairs become entangled to technology’s development as well. With an imminent catastrophe, it becomes necessary to look from another perspective of how one lives within the system today. Political, historical, and even scientific beliefs have become more than ever malleable, politicized, and polarized. Out-of-body simulations acts as a lens; a metaphysical experience; a culmination of these assumptions.

Working within the current situation of physical isolation and existential dread, it is inevitable to witness different events on-screen. Humanity is in the midst of global crises: climate change, post-truth politics, and the coronavirus pandemic. These have resulted in a spring of corrections, reforms, and revolutions in different parts of the globe and different factions of life and society— with outcomes resulting in either sustained peace or increased violence. Some have been repressed, others successful, and a number has blown out of proportion. As many suffer the consequences these events entail, some benefit from all the chaos and oppression as well.

As society transitions into a probable dystopia, Uy presents a video sculpture— one iteration of this project. Astral Prison (2021) embodies a society that has consented to plunder and pillage, deception and tyranny. All that is left is a masqueraded life simulated as digital, posing as authentic and rendering everyone blind from reality. Imposed by the few people in power, the Astral Prison encompasses the physical, digital, and even the spiritual. It manifests itself as a prison without walls; its warden ruthless and manipulative, the shackles and chains invisible, and the sentence inherited generation after generation. It is our burden and our crime; the curse of being born, struggling and consuming to survive, that we are given a life sentence. It is something that cannot easily be perceived yet it is so evident; one that makes us believe that we are truly free.

RM DE LEON

3/15/2020 Human-Nature-Industry

On March 15, 2020, we were thrown into a world that we'd never experienced before. The familiar patterns of everyday life were suddenly disrupted. Confused and anxious, we only know that we are dealing with a menacing enemy that forces us to be isolated. We have no reference to make sense of the disorienting situation, which feels "surreal."

To combat the sense of vagueness and aimlessness of daily life, RM de Leon approaches art-making as a routine to assemble his life. The exhibition presents a selection of works on paper that the artist made since the first day of the lockdown in Metro Manila.

Stains, splashes, smudges, brush strokes, doodling, and cutouts of cartoon images, De Leon employs the visual languages reminiscent of Surrealism. His involuntary mark-making is akin to the technique of automatism combined with collage, which is grounded in the idea that a person's subconscious could be more mighty and reliable than any product of conscious thought. While the organic expressions of materials and the energy of the artist's marks stimulate the viewer's senses, overall abstraction invites free associations and interpretations. Thus, De Leon's work unlocks the viewer's imaginations suppressed under the conscious mind's control.

Spontaneous hand movement leaves the traces of De Leon's nightly observation of the unprecedented and unforeseeable situations, securing a meditative space for the artist to comprehend and accept reality. Marked by the subtle yet rigorous tension between the controlled and the uncontrollable, the resulting works reflect the artist's criticism of the otherworldliness rendered by the irrational speeches and actions of the world leaders, which isolate and jeopardize the lives of people. The smallness and fragility of De Leon's work represent the vulnerability of the human body. It engages in dialogue with the viewer, who is simultaneously the eyewitness to the surreal situations happening in this very moment. (Mayumi Hirano)

PETE JIMENEZ

Bed Capacity

A bed of collected, used gloves comprises a telling narrative. It is, more so, when this said bed is placed within the confines an exhibition room in a gallery – the room becomes an allusive space. Perhaps, even more telling, the result is a covert critique of our present day circumstances.

A bed and an obsessive number of used gloves that are meticulously assembled into a lattice mattress is a surrealistic visual. Perhaps the said image makes for a totemic memorial for the things that has come to pass, and, or, yet to be?

Urgently tackling the matter, the exhibition title “Bed Capacity” is culled from the relentless television and social media barrages announcing the state of full occupancy of the emergency rooms and patient wards. This is the aftermath of the exponential outbreak of the COVID virus in Metro Manila, and other cities and provinces in the country.

For artist Pete Jimenez, the cathartic trigger to use the bed as an object and image for an installation piece came from his indirect, yet difficult, experience during the ongoing pandemic. A senior member of the artist’s family was in dire need of emergency medical assistance (due to another illness) and they found themselves anxiously rallying from one hospital to another as these were filled over and beyond its capacity.

Artists at different times in art history have used the image of the bed to convey various themes, ranging from a person’s alienation due to the increasing rise of industries and commerce in the middle of the 20th century; to modern works of art in the same time frame (1950s) that saw in one artist’s work the pivotal use of the bed as a literal object that paved the way for the further development of painting as an experimental medium; and in the post-modern and post-conceptual art years (1990s), it was featured as a representation of libertine activities and its subsequent angst experienced by a segment of the youthful generation.

Previous exhibitions has seen Jimenez’ guile in negotiating the opposite poles of the esoteric and the vernacular, while mainly focusing on the latter. Employing an aesthetic that rummages consumer debris and other historical-valued, and not, found materials, the artist has brilliantly juxtaposed these with slogans, buzzwords, and urban clichés that spring from the current issues that define our popular culture. Jimenez is quick on his feet and abundant with wit in recognizing the puns, both visual and literal, that make the connections for these, and thus delivering a satirical and darkly humorous commentary. In “Bed Capacity,” it is all of these once again, and the artist remains not turning a blind eye to the pressing, and timely, needs of the moment. (Jonathan Olazo)

ALT PHILIPPINES 2021

Pause to Reframe

This year, ALT Philippines offers you a pause. Pull things into view: exhibitions, education, and experiences—and reframe your perspective.

Join us for the opening of ALT Philippines 2021 December 4-8, at Finale Art File, Makati City.

ALT Philippines is a collective of 9 galleries:

Artinformal @artinformalgallery

Blanc @blanc.gallery

Finale Art File @finaleartfile

Galleria Duemila @galleriaduemila

MO_Space @mo_space

The Drawing Room @drawingroommanila

Underground @underground.gallery

Vinyl on Vinyl @vinylonvinyl

West Gallery @westgallery

CHRISTMAS GROUP SHOW

Raena Abella

Johnny Alcazaren

Poklong Anading

Aleah Angeles

Bert Antonio

Antonio Austria

Pope Bacay

Jan Balquin

Pablo Biglang-Awa

Ringo Bunoan

Annie Cabigting

Valeria Cavestany

Mariano Ching

Joey Cobcobo

Francis Commeyne

Louie Cordero

Jigger Cruz

John Lloyd Cruz

Lec Cruz

Kawayan de Guia

Neil de la Cruz

Pardo de Leon

Joey de Leon

RM de Leon

Bembol dela Cruz

Rocelie Delfin

Ranelle Dial

Yasmin Sison

Gerry Tan

Patis Tesoro

Van Tuico

Clairelynn Uy

Miguel Lorenzo Uy

Mac Valdezco

Gail Vicente

Marija Vicente

Victoria

Oca Villamiel

Judelyn Villarta

Liv Vinluan

Paulo Vinluan

David Viray

Welbart

Jemima Yabes

Atsuko Yamagata

Jared Yokte

MM Yu

Abi Dionisio

Rudolph John Doane

Beejay Esber

Dex Fernandez

Pancho Francisco

Rodolfo Gan

Lyra Garcellano

Mark Andy Garcia

George Gascon

Ayka Go

ND Harn

Johanna Helmuth

Nilo Ilarde

Eugene Jarque

IC Jaucian

Pete Jimenez

Winner Jumalon

Taichi Kondo

Romeo Lee

Jojo Legaspi

Tiffany Lafuente

Robert Langenegger

Muchi Lao

Jojo Lofranco

Edwin Martinez

Keiye Miranda

Jason Montinola

Raffy Napay

Poch Naval

Manuel Ocampo

Nikki Ocean

Kim Oliveros

Rhaz Oriente

Lee Paje

Lynyrd Paras

Neil Pasilan

Michelle Perez

Zoe Policarpio

Garryloid Pomoy

Miguel Puyat

Richard Quebral

Ling Quisumbing

Mark Salvatus

Geremy Samala

Julio San Jose

Arturo Sanchez

Luis Santos

Soler Santos

Mona Santos

Isabel Santos

José Santos III

Carina Santos

Pam Yan Santos

Jojo Serrano