Kim Oliveros

Neil de la Cruz

Rocelie Delfin

Kim Oliveros

Neil de la Cruz

Rocelie Delfin

CHARLIE CO

System Corrupted

System Corrupted in an unparalleled time, when a virus that broke out radically changed the world and challenged all systems, Charlie Co reflects on the fragility of the world, humanity, and the human within the systems. The body of work in this collection was created between 2019 to 2023 where Co chronicles a period of premonition, the dark pandemic crisis, national and global concerns of the time, his uncertainties on his faith, and questions on the system of the artworld.

Dark and unwary, sincere and surreal, the works are filled with the artist’s visible energy sensed through the strong textures and blazing colors. The works are monumental, encrusted with symbols that form narratives within narratives. The sizes are formidable, intended to draw its viewer inside, to be one with the images, to create his or her own story from the images.

In Reflecting De Bruyckere (2019) Co confronts the frailties of existence and freedom, of life and death. In The World Gone Mad (2020) he journals going through the pandemic and the events within the peak of the lock down. The Cross Series (2022) express a period of self dissecting his faith. Do We Have A Choice? (2022) questions: What did we do to the world? Do we want this? In Paradox (2023) he questions the institutions and players of the artworld and contemplates on the role he plays as an artist inside the system. The installation of the massive matchsticks holds together the message of the artist: life is fragile, the world is fragile.

But the artist can only tell his stories. On how to see and interpret these stories, Co calls upon the viewer to make a personal reflection and make the interpretation.

(Moreen Austria)

GOLDIE POBLADOR

Fertility Flowers

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Glass, scent and video

In mythology across cultures, women’s bodies are transformed into plants as punishment for acting on their desires and taking agency over their own bodies. In Philippine folklore, these cautionary tales have perpetuated the archetype of the submissive, virginal Filipina—her personhood contingent on her willingness to conform to the social mores of the time.

Fertility Flowers is an interactive installation of glass, scent and video that interrogates the origins and mythologies of several flowers native to the artist’s home country, the Philippines. In the tale of the dama de noche (Cestrum nocturnum), a queen is unable to produce an heir, and in her desolation, becomes a night-blooming flower. Meanwhile, colonized West Indian women used the peacock flower (Caesalpina pulcherrima) as an abortifacient so they would not bear children into slavery. The cadena de amor (Antigonon leptopus), whose name translates to “chains of love,” came to represent the moral puritanism Filipino women were bound to during the Spanish era.

Poblador follows a throughline from her earlier ecofeminist oeuvre, including Venus Freed (2015) and The Myth of the Ylang-ylang (2015), which showed how flowers such as the ylang-ylang (Cananga onorata) are taken from their countries of origin and appropriated through trade. In Fertility Flowers, she turns this lens towards reproduction as the crux of centuries of subjugation women have suffered at the hands of colonial and patriarchal powers. In her glass sculptures, figures of women emerge from fantastical, petaled forms as floral scents waft through the room. In the accompanying film, Poblador herself slips into the myths of these flowers to commune with the women at their center.

Drawing parallels between these florae and the colonized female body, Poblador turns the myths on their heads to imagine the Filipina prying agency from her oppressors and blossoming towards emancipation.

(Apa Agbayani)

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to the Oakspring Garden Foundation for your awarding me with the time, space and support which allowed me to finish this exhibition. This project was also supported in part by a Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grant.

Thank you to the Fertility Flowers Film Collaborators:

Director of Photography: Sasha Palomares; Creative Direction by Apa Agbayani; Character Design, Hair and Makeup by Slo Lopez; Production Manager: Tony Battung; Edited by Abby Alcanzare; Color Grading by Bianca Francisco; Music composed and performed by Michelle Sui; Mixed and mastered by Zach Rosenberg, The Queen’s Royal Garb: Carl Jan Cruz and Namì.

Thank you to Apa Agbayani and Joseph Sousa

ISABEL SANTOS

An Idea of an Idea, A Memory of a Memory

The series of work in Isabel Santos’ An Idea of an Idea: A Memory of a Memory came into fruition during a flight back from Taiwan in 2015. Based on photographs of the formations in Yehliu Geopark – large, otherworldly limestone structures – which she fixated on to stave off anxious thoughts about her fear of flying. At the time, she had only begun her medication for mental illnesses diagnosed only in her adult life.

Here is a period where she had been trying to find a way to live life with her newly prescribed medications and maintain the balancing act of her mental states. When you are in a state of distress and you find things that help you cope with these feelings, there is immense pressure to protect the fragility of the ecosystems you have built around you to protect yourself from further unpleasantness.

Despite having a cocktail of medications that she could rely on when on the flight itself, she still had to deal with the anxieties that come with waiting. Drawing came as a distraction, but Isabel soon found out that the act of focusing on an image meant that her mind was working and still couldn’t relax. Eventually, she stopped looking at images as references, and let her intuition guide her hand on the page. The tension in her brain eased, not unlike when she gets them when she reads. It soon became a form of meditation for her that she could count and rely on to ease her fears.

When she makes these pieces, Santos remembers the saying: Idle hands are the devil’s playground. She believes, to an extent, that it’s true. “When I have nothing to do, my mind goes to places I’d rather not have it go.” Doing these meditative drawings, where she empties her mind of everything except for the task at hand – making marks on a page – is meditative and calms her anxieties. They give her a focus that doesn’t strain her brain. For her the images produced are like visual representations of her brain. Perhaps her memories, rendered in a code only she can read.

(Ina Santos)

Isabel Santos has been showing her work since 2013, and has since participated in exhibitions held in Manila, Berlin, New York, and France. She was the grand prize winner of Uniqlo’s UT Grand Prix Competition, which was held in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, in 2020.

ROBERTO CHABET

House Paintings and Drawings

In 1961, Roberto ‘Bobby’ Chabet had his very first solo exhibition while briefly working as an architect under Angel Nakpil’s firm, which happened to be the same office that was tasked to reconstruct Manila after the war. Although Chabet decided not to pursue a career under the field he held a degree in, he was surrounded by many great practitioners whom he considered influential in taking on the herculean task to give the city back its identity—a task that he might have considered as a significant opportunity to embrace instead the values of modernity: not to re-construct tradition, but to draw and build from the ‘ruins and psychic debris’ that were the true state of things within that moment.

Instead of architecture, these values would then find their way into his art. One of the more prominent works wherein they would manifest was in a series of untitled works referred to as ‘house paintings,’ which first appeared in 1969. Chabet had always treated art, in any medium or form, as an ongoing process. Which explains some of the recurring subjects and shapes, whether found in his drawings, collages, installations or objects. The repetition through different drawings and paintings of this familiar pentagon-shaped image would then become one of the iconic works in Chabet’s long and productive practice.

The shape that has very much resembled the pictograms of houses draws an irresistible connection to his primary inclinations toward architecture. Was he ever intrigued by the praxis of his initial craft? To build something useful and profoundly essential as a shelter? According to the show’s curator Nilo Ilarde, Chabet might have been less interested in the function of architectural structures like houses, but rather more on art’s lack of practical use.

Throughout his body of work, Chabet had seemed to have extracted the vital components in house constructions to render them as art, useless and dissociated: plywood, nails, hollow blocks, galvanized roofs, sheets of metal, and shelves. Stripped to their bare appearances, they appeared as anti-monumental, as against the whole, and more indebted to the cause of autonomy and simplicity of rarely celebrated building blocks. It could be stated, argumentatively, that they are the expressions of what seems to be an orderly collapse—his projects that use construction materials, which come out as coherent, restrained, and stark.

It will always be a case for wonder: on whether Bobby Chabet participated in any real and practical design for a house, and whether these art objects were made from such fantasy or predisposition. But in the way he presented his works throughout his career, as raw and as straightforward as they are, he always insisted that they were never meant to represent any real thing. They were always devoid of any illusions—mere lines, shapes, and drawings. As indexes. As decoys. ‘Art as decoy', which was one of the prevailing concepts in most of his exhibitions.

Therefore, the house that was built, as the saying goes—is not.

/CLJ

OCA VILLAMIEL

Quiet Earth II

The moon does not always appear in the sky. When the heavenly body hides from view, what takes its place is a deep mystifying blackness, or on some nights, a glittering expanse, dots of starlight from which other lights, other colors might appear. Biblical writing suggests that the world begins in this way: in the willing of light from absolute dark, in the dawn of nature. Life, too, continues in this way: the spirit passing quietly through skies, beams, rocks, mountains and rivers, through deep caves where centuries echo, and still ponds where silence dwells.

The spiritual world has its mysteries and so, too, does the visible. Through art, Oca Villamiel explores how the material might hew close to the natural, and how nature might offer a trace of the spirit.

Nature’s material presence evokes the immensity of a world that is given freely. How do human hands come to cherish and care for this living world? A sacred provision, in another biblical passage, is expressed in the image of the dew of Hermon. From great snowcapped mountains, the dew flows South, blessing the far lands. An image in nature takes on symbolic meaning, but in painting, its presence is atmosphere. Globules of white, appearing across fine blots of gray on a wide expanse of canvas, invites optical absorption. Paint, as material, creates an impression of the natural, the hint of cool air and bright dew which seems to generate its own existence.

Eastern philosophies have inspired Villamiel’s spiritual practice as well as his sense of beauty. The belief that the sacred dwells within nature invites an attitude of respect and earnest attention. Here, art yields no representation, but only an evocation of nature’s processes through form. A haptic surface intimates turned earth. Texture, which implies time, embodies the weather-worn surface of a slab of stone. On the ground are ochoko, small sake vessels that the artist has collected for more than a decade. They are a humble nod to gathering: the gathering of guests for one special occasion, and the slow act of gathering materials within a stretch of time.

Scattered in a circle, joining the earth, the vessels call for a quiet meditation: to turn to the earth, to the stars above, and the land below. An ode to the spirit, ever turning.

Pristine L. de Leon

GEREMY SAMALA

Ephemeral Bliss

Fleeting, fleeing, feeling

Beauty and happiness are brutally transient, as recent past and current events have inevitably taught us. The greatest delights might vanish in an instant, drowned in ebbing uncertainty. This idea has inspired artists throughout time, defining their endless fascination with still life. Even Charles Baudelaire, one of the finest minds of the 19th century, plainly states, "extract the eternal from the ephemeral," demonstrating his profound understanding of human nature's propensity to preserve a life-changing experience.

In Geremy Samala’s Ephemeral Bliss, still life is what remains of his exploits in figuration and a manifestation of his life’s passion. Understanding that his paintings express an ongoing process that is shaped more as a vocation than a profession, he asserts his fealty to this genre, transforming it to make it all his own. Thus he fills his neon bouquets of stargazers and other floral hybrids not only with foliage but also with stars and quasars; fluorescent pink cacti boast proud blooms of sparkling petals; a flower shares its vessel with both greenery and a raging flame. Samala tears the horizon and places portals to multihued elsewheres, desert skies combining their glorious colors with a glimpse of night. The artist cleverly guides the viewer’s eye towards vastness and infinity, serving as reminders of the impermanence of life. Cracks and crevices show the passage of time, the inevitability of decay, and the fragile nature of existence, interspersed with fluorescent lines and grids loosely applied by the artist’s hand. Beyond the brokenness, however, he offers escape through entryways to the cosmos, a symbol of the infinite and eternal. The still-life flowers, arranged in various compositions and manipulated forms, call to mind both imperfect and temporary beauty, meant to be savored and enjoyed while they exist.

As Samala continues to learn about the traits and intricacies of his art, we are encouraged to join him on a personal voyage of discovery. We see how plants have emerged as one of his favorite subject matters to paint and how these connect him with the fundamental elements of life. By generously sharing his explorations, the artist also presents a greater appreciation for his natural surroundings and ruminations on the human experience as a never-ending journey of inquiry full of highs and lows, accomplishments and failures. Through the distinct energy that reflects the artist's state of mind and feelings in his works, Samala enjoins us to find deeper fulfillment, meaning, and acceptance in the recognition that life is intrinsically flawed, as we grant ourselves permission to capture joy in impermanence.

Kaye O’Yek

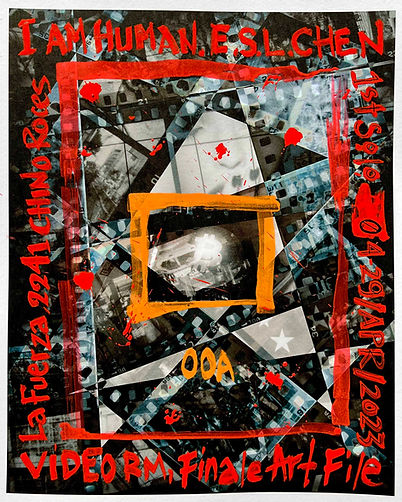

EDRIC CHEN

I AM HUMAN.

My name is E.S.L. Chen.

I AM HUMAN.

“It started with trusting screens.

Those who could, projected perfection. We

stopped questioning what we see. Then,

everyone followed blindly.

They conditioned us—

To want the same things, to

look the same way,

to feel the same colors, to

think in straight lines, to

talk in one voice.

Nothing escapes modification.

Our lust for unity has cleansed our carnality. Yet,

we push on unabated.

We boldly call it progress—

A progress we are afraid to define.

What does it mean to be human?"

These photographs are digital reproductions of a physical medium, the black and white film negative. My process goes beyond what a traditional photographic enlarger can resolve because it lives in between realms. Nothing is truly pure, yet my subject matter consists of my impulses —that which houses the infinitesimal possibility of the existence of the organic self. To that, I added the choices to use one black box, one lens, one type of film, and a commitment to the abandonment of modification, yet one issue remains: Does the journey from analog to digital and the conversion back to an analog medium, that is paper, enough to preserve immaculacy?

I exist simply to make copies of copies.

"Nihil sub sōle novum."

("There is nothing new under the sun".)

KIUKOK, LEGASPI, MALANG, OLAZO

Four Masters, Four Worlds: Revisited

Finale Art File marks the occasion of its 40th anniversary with Four Masters, Four Worlds: Revisited featuring Ang Kiukok, Cesar Legaspi, Romulo Olazo, and Malang. Aside from commemorating this fellowship among equals, this exhibition represents a significant milestone for the gallery as it was the first-ever show Finale staged when it was still located at Sunvar Plaza in Makati City in 1983. It continued to be held annually until Legaspi’s death in 1994. Then as it is now, Finale has been championing the works of artists going against the grain of the established conventions, expanding the possible, and reconstituting the terms in which the contemporary may be interpreted and re-imagined.

The choice of medium for these masters known primarily as painters of compelling narratives onto canvas is telling as Finale, when it began, initially offered works on paper. Using their respective pigments of choice, the artists rendered their characteristic styles on this delicate medium with no loss of verve, distilling their subjects and forms to their rudimentary essences, and fully utilizing the compact universe of flattened fiber. It’s not hard to visualize that a few of these works may have been accomplished at the same time, as these masters were known to bond during their numerous drawing sessions.

Four Masters, Four Worlds: Revisited acknowledges the legacies of Ang Kiukok, Legaspi, Malang, and Olazo who, to a significant extent, shaped the reputation of Finale as one of the foremost registers of contemporary art. The gallery looks back at the past not out of nostalgia but of tender affection for these dearly departed artists who, beyond their medals and towering statures, were friends to Finale’s founders. They shared stories and meals in their respective studios and homes and at Sun Moon Restaurant in Greenhills, their favorite hangout place. That may be a world away, but this exhibit brings it a little closer.

(Carlomar Arcangel Daoana)

GALE ENCARNACION

Season of Disbelief

A theatre stage, not lacking in its parts such as a backdrop and its curated props, is simulated and revolves around a backbone consisting of a triumvirate of parts that are composed of appropriated images and objects, perhaps arbitrarily culled with an air of artistic whim and chutzpah, from various points of cultural history.

The first of the three is a mural based on an Ukiyo-e woodblock print made in 1889 by the Japanese artist, Adachi Ginkō. The scene depicted in the woodblock, titled “Illustration of the Issuing of the State Constitution in the State Chamber of the New Imperial Palace” exudes the pomp and luster of any given formal function, especially if the host is the state governing body. It is interesting to note the motive for such an appropriation: is it merely a source reference for a painting that needs models for luxurious decor, elaborate ornaments, and dressed up officials and members of the elite class; or does it also entail a hidden, politicized agenda?

It is clued in by the artist that the gallery’s physical attributes, which is a uniquely elevated space perched above another exhibition area below, led the artist to make this “mock theater,” as it “looks like a stage.” It is not far fetched to surmise a critique ensues from within, and highlights the powerful influence a gallery has as an institution of arbitration. The mural piece, given the title “Public Relations,” may very well have these subtle questions rooted in its trenches.

The second part in this “theatrical arena” is a meticulous variable work in terms of its hefty coverage, quantity of parts and hours spent for its production. Consisting of soft sculptures made of velvet and sewn in the essence and shape of fire and flames, “Feud,” is a humorous reference to an appropriated narrative, a controversial story which involves “Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli wherein both were at a costume ball and the former asked the latter to dance, and then danced straight into a lit chandelier so the back of Schiaparelli’s dress caught fire (Encarnacion).” With both parts providing context and feeding off each other, the artist’s thematic narrative has more clarity. Is it a shot in the dark about fleeting vainglory, of which is considerably the nature of the beast, of the muse called Art?

There are many ways to get at the skinny, or a better expression, to skin the cat. This does not make fun of but rather pays tribute to the artist’s love for felines! (This writer remembers she took care of strays while she was still matriculating at the UP College of Fine Arts, where she was an exceptionally talented artist.) Encarnacion belongs to the very youthful generation of artists whom Conceptual artist Alwin Reamilo described as the product of her alma maters’ primary impetus: to “build the Perfect Beast,” or, in longer verse, a complete artist endowed with drawing and painterly skills and has been trained to think and be critical.

Gale Encarnacion’s early forays had her examining the nature of materials other than traditional oil paints often associated with painting, and thus was able to weave brilliant tales and narratives from common materials she found handy: bread, cookies, plastic wrappers etc. Showing her range as an artist, it was also natural for her to draw inspiration from visual questions and problems that proliferated the subjects around her curriculum.

Perhaps, post-collegiate life has posed its own issues and she has been quick to recognize and make sense of the arena and industry she finds herself in. In a way, she has turned her critical aesthetics to the dissection of the artist’s life. Thus, perhaps too, the installation piece “Season of Disbelief” is her assessment and notes to self of what’s going on. The artist and sculptor Damien Hirst, perhaps one of invincible personalities of the YBA, once said in a printed interview, “Art is about wanting to live forever.”

Making use of her adapted and honed fabulist aesthetics, Encarnacion has taken on one of art’s inevitable and romantic themes. A handful of artists of recent practice would attest to the higher difficulty handicap of such intangible themes; over the easily accessible themes with labels and handles, ranging from still life painting to art practices having advocacies, which make thematic subjects easier to discuss objectively. There is nothing lesser about these, and the point being is that to take on more abstract themes is more likely to dance with the devil and commit career suicide. She has bravely followed her gut on this dive.

“Season of Disbelief” is an installation with readable associations but it must be intended by the artist to be open to interpretation. It may be riddled with the backstories and biases incurred in the artist’s picking of images and objects, but a person once immersed in the light-hearted and whimsical geist of the work will be delightfully amused, if not inspired. A point of interest with regard to the artist’s strategies is her seemingly employed system of indexes that skin the theme of a subject by espousing tertiary or third-degree removed representations, which makes the reading of her satire more complex and seductive.

The installation has explored the aspect of the gallery involving its utility for sharing. It is no longer just a neutral space but is a sanctuary of sentiments. Appropriating, too, the installation’s title from the famous American writer Ray Bradbury in one of his short stories, it reflects the change of attitude and mindset of the main protagonist, with whom only an old soul or a man downed by life’s seasons will identify with. Summarily, one of the themes besetting Encarnacion’s theatre is the pain of loss, of losing one’s self, and of losing, with the finality of ending up facing a specter of a vacuum where its shape has been dented before repair. To satirize these depths is maybe a way to force one’s self back to community. And for that person who has just gone in and experienced the installation will highly appreciate its fanfare and comedic spirit, and just maybe, will realize, like some of us have, that the artist has hit the nail on its head at poking fun at our foibles, and egg us to rise above it. (JO)

DENISE WELDON

In the Quiet Spaces: An Invitation

Come.

Let the small coins of sound fall

And gather around your feet

And consider it a blessing.

Somewhere, a bell swings

Its one sweet note,

But it’s not yet calling your name.

Let the white veils of silence

Lift and turn, revealing

The crosses a window bears,

The transparency of glass.

Beyond that is a garden

Where the sun infuses each leaf—

Fully and unconditionally—

And does not break it.

A tree has wings because of birds.

The world has a heart because you inhabit it.

There’s a room where

No permission is needed

For you to fully wear

The skin of your soul

And see through eyes

That perceive

That the many layers of cloth

Are simply passages

Of the same light.

(Carlomar Arcangel Daoana)

GROUP SHOW

when the past is always present

The passage of time brings bittersweet comforts— when fleeting moments become lingering memories, when lengthy nights no longer amount to our shorter breaths, when the past is always the present. The participating artists in this exhibition imagine and give definite form to an abstract concept such as time. Kim Oliveros, curator of the show, retraces the childhood joy in a place that has gone through physical transformation. In his painting, the flowering vines taking over a deteriorating wall, adorned with butterflies, encapsulates the passing period and the link between the past and the present.

Rhaz Oriente’s work responds to the actual site of the exhibition, the Finale Art File, where she also had her first solo presentation. Her lightbox is an optimistic reminder of the beginning and continuation of her own artistic practice. This sense of continuity emanates from Kim Hamilton Sulit “Back to the Old House II: I and II” in an attempt to reclaim narratives that are deeply rooted in his internal conflicts, and in spaces and structures that informed his domestic experience. Jomari T’leon considers his relationship with time as a potent factor in mending the self after enduring a personal struggle. For T’leon, the particular narrative in his painting and art-making both unfold over time.

Touching on familial bond, Garryloid Pomoy remembers his younger years spent with his mother while making cloth rugs they used to sell; time, like cloth rugs, gets overused and remains unrestored. Ayka Go revisits the idea of home through an object she associates with a family member: a reusable cookie canister turned into a sewing kit. Wrapped and concealed from the viewers, Go’s object of contemplation becomes a symbolic image of a retrieved past.

Former botanical illustrator at the National Museum of the Philippines, Rolf Campos mindfully arranges illustrations of species of plants in reference to their 16th century depictions. Appearing more alike despite their obvious differences, the arrangement of plants by row is his approach to rethinking their present-day importance in an era of climate change. The process of gathering and imitating images that represent the role of digital media in modern life prompts Valerie Chua to portray her subjects engaging in mundane and leisure activities. She delves into contemporary expressions of nostalgia and memory through shapes and hues.

John Marin establishes paralleled events and experiences among indigenous peoples who are often subjected to violence for defending their ancestral lands. Marin’s “Fire to fire, land to hand” takes notice of this seemingly cyclic aspect of history. In a series of stereoscopic images rendered on mirror, Sid Natividad offers a visualization of the recent oil spill in Mindoro. The immersive and realistic experience in viewing his work reiterates the long-term effect that will continue to take a toll on marine life for years to come.

How long can the mind hold onto the past and the ongoing moments of existence? Luis Antonio Santos, in a continuation of his prints on plexiglass and silkscreen painting of fragmented jungle, further examines the capacity and fragility of our memory to remember and forget. The imprint of a seascape manifests a certain state of tranquility and calm in Lou Lim’s visual record of time. In her own contemplative recollection, Lim extracted and painted images of a seascape— its surface a form of stillness.

Their individual interpretations of the different yet overlapping timelines, the past and the present coinciding, give a glimpse at current realities or into foreseeable futures.

James Luigi Tana

ABI DIONISIO

Red Is Not Red, Blue Is Not Blue

There are visible, sometimes subtle yet very much felt, manifestations of remnants from our shared ordeals in the past years: the lingering fear for one's health; discomfort in large crowds or closed spaces; waves of grief; precarity in sustaining and providing for our basic needs. The idea for the ongoing exhibition was developed during the period of a global pandemic. Here, the artist Abi Dionisio presents our acquired anxieties using delicate imageries to encourage us to think about our experiences with critical distance and empathy. To animate our art encounter, she activates perception and instructs us to view her works in close proximity and from a distance. She quotes Miyamoto Musashi:

“Perception is strong and sight weak.

In strategy, it is important to see distant things as if they were close and to take a distanced view of close things.”

As a painter who is trained in hyperrealism, Dionisio inevitably excels in her career, able to elicit awe and admiration from various local and international art platforms. Her father’s health crisis in 2013 made her decide to use embroidery as method and subject matter in artmaking, exposing not just the finished and polished, but also the tangled and unkempt. Her family’s livelihood in Bulacan comes from sewing. Growing up, the artist was surrounded by sewing machines, bulks of textiles, colorful threads, needles, and tireless, skillful hands that create clothing for teachers, students, and athletes. This role in the community perhaps grounds Dionisio’s ideations: home, security, space, domesticity, persons – their faces and their necessities. She is as well interested in depicting journeys, distances, destinations; layering symbolisms, thus, intentions. Imaginably, these are narratives of coming home or traveling back home; these navigations are not always peaceful.

The concepts attached to each object in this space are embodied in Dionisio’s creation – intimate and bold – as seen in her modest embroideries and the breathtaking large-scale paintings. The contrast is balanced, unsettled even, by the grandeur of an installation work depicting a rainbow made of lace, a vast cloud, and underneath it, a boat-shaped wishing well. With her intricate handling of materials, the “working with rather than a doing to” is emphasized. Thought process is made visible as we consider the motivations of the laboring hands: place in community, care for others, love for family, home.

(Con Cabrera)

WELBART SLOWHANDS

Overview Effect

In a 2019 feature article titled The Whys of Slowhands, the origin story of the self-taught painter Welbart Slowhands was narrated. From his childhood drawing of helicopters and fishes, his exposure to local religious paintings inside the church of Paombong, Bulacan, and his eventual nursing practice, the artist recalled how he fought for time to hone his skills in painting. This proficiency was and is his tool to share what he learns about life. It took him decades of searching for the self, struggling for his art, and going through loss and grief to arrive at a state of calm and surrender. Because life happened/happens to the artist, the hollow blah blahs in his paintings of texts became words of positivity, often love love love.

The artist has learned to transform his attitude and thinking by cultivating knowledge about the world. This exhibition is an exercise in stepping back. Welbart wants to communicate how a change in perspective can be achieved by distancing oneself. He is inspired by the wabi-sabi aesthetic of seeing beauty in imperfection as an ephemeral feeling. The transience he extends to the overview effect, a concept the artist is also emphasizing in his new series of works. This phenomenon is said to be a shift in perception that happens to astronauts when they see Earth from space; it is self-transcendence as the eyes witness the power of visual stimulus. For the artist, his first experience of going to the beach and seeing the seamless transition of land to coast to water to the horizon to the sky is seemingly comparable. A moment of sublime experience is something to periodically come back to as a reminder of our smallness in the vastness of the universe. To remember is imperative in this demanding, material world; it must be profound to not be defeatist.

(Con Cabrera)

NILO ILARDE

unpainted painting

In unpainted painting, Nilo Ilarde endeavours to give emptiness a shape. Occupying all three spaces of Finale’s gargantuan warehouse space — an intimidating feat for most artists — these pieces reimagine art that rejects commerce and the artist’s impulse to fill a space up with objects, and instead approaches the gallery, the White Cube, as a readymade in itself.

Ilarde’s artmaking process often involves tedious and fastidious planning where, during the ingress, with time so close to the opening and unveiling of the work, there can be no errors. But, this comes with the acceptance of the fact that errors are a part of the process. There will always be unforeseen circumstances that require a response that may change the work and its meaning in the end.

Here, he excavates and reworks all three spaces of Finale, and in the process, uncovers built and obscured histories, recognising the preciousness of stillness and contemplating what can grow from it.

“Philippine Deep” occupies the Tall Gallery where Ilarde excavates a one-foot square cube of the gallery’s concrete flooring, and situates a ruler — a tangible symbol of a line that extends indefinitely — in the space made within the existing space, invoking notions of limitlessness, the emptiness of No Man’s Land, the unmined and the unexplored.

The ruler, a whisper of Walter de Maria’s “The Vertical Earth Kilometer”, shown in Kassel, Germany for documents, and Constantin Brâncuși’s “Endless Column”, Ilarde extends downward instead. It is propped up by scaffolding crafted by fellow artist Bernardo Pacquing. Sometime after the exhibition, the debris from the excavation will bury the ruler within the gallery’s foundation, forever invisible and insensible, but an addition nevertheless to an already rich history.

In the Upstairs Gallery, words by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist remain after the rest of the walls are stripped of the layers of paint that change exhibition after exhibition, exposing the plywood underneath. Entitled “FORGOTTEN CENSORED MISUNDERSTOOD OPPRESSED LOST UNREALIZABLE”, these words put to the fore works from the past and present that often escape recognition from artists, curators, and gallerists.

This is another kind of excavation, and a method of expression that Ilarde has utilised since 2001 for a show at the CCP Small Gallery. Peeling off the paint, you create something new through subtracting from what is already there. At the same time, you encounter the scars and holes from nails and hooks made from the gallery’s previous shows, uncovering material histories while inflicting an almost violence on the space a new one.

Like he does the white cube, Ilarde perceives words as readymades themselves, and the spaces between them as voids, necessary for the words to be understood.

The Video Room is transformed into a viewing deck, where it becomes an uninhabitable, protected site. “I AM INSERTING THIS ROOM ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST AS A PROTECTED AREA” attempts to reinstate the gallery as a sanctuary, as inspired by artist and environmentalist, Amy Balkin.

Ilarde asks, How do you reinvent emptiness? Yves Klein created “The Void”. Robert Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning drawing. Marcel Duchamp bottled up Paris air. Over the course of his career, Ilarde has alluded to emptiness through the vessels that have been emptied — paint tubes, souvenirs from defunct buildings — signals of the aftermath. Ilarde believes emptiness and silence should be protected, keeping the words of Douglas Huebler close whenever he creates: “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.”

And yet we can’t help but still make.

Confrontation with emptiness invites contemplation. What do you think about in the presence of absence? When there is nothing before you that inspires your own projections, what do you have other than your own faculties to make sense of the world and your place in it?

Experiencing an empty space is more precious than putting in a painting. “There is always a nail in a wall somewhere that can take a painting.” The void, emptiness, space: this allows what it surrounds to be illuminated. Set in contrast to nothing, some things are made visible.

Ilarde, who has only begun using search engines in the last three years, says, “We have no unassailable authority, standards, or universal truths. No one is ever right all the time. Every opinion is there to be challenged. With social media, it has become so much easier to do so.”

There is circularity in history, but there is circularity in commerce, too. Ilarde’s ability to pursue and create work that elides straightforward commercial valuation is only made possible by creating work that does contribute to commerce.

This work by Ilarde, viewed in its entirety, perceives the gallery — the white cube — as a readymade, and to consider it, in itself, as both the subject and object, and not just a vessel that holds other objects. Galleries give us space, all we do is fill it up. Taking his cue from Robert Smithson, Ilarde creates meaning by emptying it out instead of adorning it, and making this sacred space both a place and an object to be considered.

All three of Ilarde’s works dare to unravel themselves, pointing towards creating something within ourselves, instead of looking for more things to own, tangibly, as we give emptiness a shape and bear witness to it.

Words by Carina Santos

ROCK DRILON

Visayan Rhapsodies 2

Mention Rock Drilon’s name among art circles and you would evoke quintessential icons and imagery of what constitute a continuum of contemporaneity in Ilonggo art.

Spanning several decades of artistic work that figured in exhibits in the art capitals of the country and even on to the aesthetic meccas around the world, Rock’s canvases are evocative of a traversing through the shifting zeitgeist of the artist as it takes him beyond the inspirations of his art to the advocacies that he champions, among which would be the advancement of art and culture, heritage preservation, and an active environmental awareness.

Visayan Rhapsodies 2 captures this navigation through the artist’s psyche and segues from a previous exhibit done in the same lines back in 2018. Featured in the exhibit are some of Rock’s definitive artworks, some of which have been commenced several decades ago only to find a completeness and readiness to be appraised by a judicious eye quite recently. Though eclectic in the selection of pieces, these artworks constitute an introspective visual bricolage – what is a rhapsody after all if not a stimulating hodgepodge of various musical motifs?

Prominent in the exhibit would be Rock’s distinctive artistic techniques reminiscent of his previous works: curls and swirls of colors in limited palettes accented by vivid patches of sharply contrasting hues and shades or sharp iterations of abstract images that seem to recur in irregular sections. These sinuous lines of varied colors snaking through his canvases hint on a continuous pathway, akin to an unbroken bike lane: it is reminiscent of that artistic journey, as mentioned above, and projects the artist’s experiences in varying layers – from the regional to the international, from creator of the art to curator of artworks.

Interspersed and juxtaposed with interjections of abstract figures and blots that appear to be milestones corrugating the sinewy pathways cutting through the canvas, these seem to evoke the things that Rock is passionate about: the flourishing and thriving of art in his native Dumangas and in Panay, in general; the maintenance and conservation of heritage sites and structures, and of course, environmental activism that advocated for the propagation of local flora and saw many a bike lane constructed to serve cyclists in the region.

Visayan Rhapsodies 2 may appear to be a completed hodgepodge, but though an accumulation of on-going experiences rendered with paint and canvas, it is still essentially a work in progress: the artist in search of himself and his place in his world – and it takes a rhapsodic melding of aesthetics and introspection to make sense of Rock Drilon’s art, then we concur and immerse in the spectacle.

(John Anthony Estolloso)

ANDRE BALDOVINO

A Land Without Signs

In abstraction, there is usually a drive to dissolve an object of representation, to lift image away from the province of words. And yet, Andre Baldovino is fascinated with language.

Language binds speakers in a relay of recognition. We know a road by its name, a sign that alerts us that we have been here before. The light turns red, a car stops. A black cat crosses our path and we take it as a strange signal of misfortune. The lived world is composed of signs: recognizable objects, images, sounds, words that point us towards something else. We take part in this daily shuttling of meaning, constructing a shared context through a habit of interpretation.

In “A Land without Signs,” the artist is moved to contemplate abstraction’s place in this process. “If a person looks too long at things that have no fixed meaning, then maybe meaning itself can become blurry,” says Baldovino. “Something gazes back and changes the way that we see.”

Baldovino’s previous exhibitions have led him to his own logic of making: He has likened abstraction to a lucid dream, where spontaneous gestural strokes are disciplined by calculated design. Working in this mode has made him curious about the locus of creation, where abstraction comes from, and what it takes for a painter to summon this place.

This new series of works begins to unsettle the stubborn autonomy of forms. Can a field of shapes—lines jutting against another, colors colliding across segmented planes—truly be a land without signs?

Edges once marked by firm lines have softened in these compositions. Loose geometries complement the opening salvo of gestures, their sure movement at times leading us to busy depths and middles. In some, the spatial demarcations do not segment the ground, but compel forms to rise off it, in that it’s tempting to make out roofs against a yawning mist and the long, wispy streaks of clouds. Is it a bay, a port? Abstraction might be a place one can get lost in, but looking hard at that pale mirage of a harbor, it can also be a place where one finds one’s bearings.

There is a famous passage from Friedrich Nietzsche that has fascinated the painter, “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.” Abstraction invites the artist and the viewer to contemplate its visions, perhaps interpret them through the signs that we know. But images that hang at the edge of recognition can also shape our habits of looking. And if we do find our way out of this land, we might find the signs unstable, our vision slightly skewed.

(Pristine de Leon)

GROUP SHOW

Mouth Words, Muster Murmurs

Roan Alvarez

Jorem Biadoma

Henrielle Pagkaliwangan

Camille Quintos

Miguel Uy

excerpts by Carissa Pobre

Silence is loudest

in a state of quietude;

we are listening.

To patiently sit with contradictions, to confront our anxieties with uncertainty, and to operate despite conflicting realities is offered in Mouth Words, Muster Murmurs. Together with visual artists Roan Alvarez, Jorem Biadoma, Henrielle Baltazar Pagkaliwangan, Camille Quintos, Miguel Lorenzo Uy, and writer Carissa Pobre, the exhibit attempts to traverse tensions palpably present yet often kept quiet. The works, having less to do with material, meander through a spectrum of concepts that contemplate on connections with community and how that is influenced by the history of our people. Whether it is from society-at-large or one’s personal expectations, what are we saying when we’re not really speaking?

I write this preliminary text one word at a time, one line from beginning towards an end, and one thought after another. A progression of words informed by what I have always known, what I’m about to let you know, and what (I assume) we could learn together. To decipher and dissect thoughts, concepts, and ideas means paying attention to what we hear, taste, smell, and see. These senses are informed by our experiences and educated by the powers around us. Nowadays, when what we used to know as fact is revisited and when what was free then is now restricted, how do we provide space to discuss what is often pushed aside or hushed? Well aware of the complications of putting words in people’s mouths, the text presented in the next few pages come from the artists themselves. Where are they coming from? What and how do they think? What do they know about the present and pressing realities? What is the work about? And perhaps, most importantly, why do they make?

Then we could trace the artist’s thoughts in their works, and ask: what have they mouthed that would muster our murmurs?

(eyb)

JASON MONTINOLA

Love, Sin, Salvation & Death

“God made man because He loves stories.”

- Elie Wiesel, The Gates of the Forest

When concepts become elusive and overwhelming man tries to ground them with the stories they make – the folklores, the fables and the myths. It tethers the abstract to our reality, a reality embellished with fantasy. The make-believe stories transform our ideals and values into something tangible, relatable, and concrete.

For more than a decade, Jason Montinola has been creating beings and entities with mystical characteristics. He is able to infuse these beings into art history, our own realities by prolifically reiterating their personas as if they have always been around without us knowing of their origins nor their existence. Imbued with symbolic and often religious significance, Montinola has introduced us to their stories, encounters with history, and their own unique narratives – their myths.

A knight like figure adorn with a mask with elongated nose, a handlebar mustache and a Van Dyke beard, he is known only by his moniker “The Sensational Painter.” This enigmatic entity’s lifelong quest for centuries is to champion the arts, seeking out novice artists and mentors them to become future masters. Throughout time he has kept the artistic passion burning and has passed on the torch of creativity from one generation to the other. In Armaturam Dei (Armor of God) we see him on a horse while holding a rapier (sword of the spirit) as if posing before a battle. Surrounding him are seven cherubs dressing him with full armor complete with breastplate and a helmet of salvation. The imagery takes inspiration from Ephesians 6: 10-18 where man is warned about the devil’s schemes and is commanded to take a stand in a battle against the rulers, the authorities and the powers of this dark world. The Sensational Painter takes on this task and becomes the symbol and the bearer of God’s might and man’s will to persist.

Dressed with a veil and a cloak, a mysterious persona has been a recurring character in Montinola’s paintings. Her/His real identity is unknown and is only referred with the phrase “Here Lies the Painter.” In multiple iterations, he/she is seen either with a half mask covering her upper face or fully covered with a cloth. He/She is said to have been a guide to artists in different time periods, from Hieronymus Bosch to Salvador Dali, he/she is able to inspire them to find their own artistic voices, their muses and their place in the art world. In “Dystera” we see him/her beside an incomplete image of a crucified Christ alongside with the martyr St. Sebastian. In it, Christ tries to encapsulate the sins of man with his body and Here Lies the Painter captures stray sins that falls off from Christ with her cloak. He/She uses his/her holy sword to kill any sin who tries to escape the cloak to protect the world from them. The arrow wounded St. Sebastian symbolizes man’s triumph against mortal suffering, a promise of salvation to those who walks in faith. Above them is a raven and a dove signifying the ever-looming presence of good and evil in the world.

Love, Sin, Salvation and Death bridges the gap between myths and our realities; between intangible concepts and the power of art to represent them; between the familiar stories we have told and the narratives we can tell ourselves. In the end it is within these stories and myths that man finds fuel to thrive and inspires him to emerge victorious. (LeCruz)

NICOLE TEE

the house allows one to dream in peace

Continuing her meditation on the immediacy of short-form content and the internet — and how the speed and mindlessness of consumption affects her and her practice — Nicole Tee looks to slowness and comfort in her recent solo exhibition, the house allows one to dream in peace. The title — taken from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space — contemplates the sanctuary provided by a space, as well as the idea that space is a reflection of the inner workings of one’s mind.

Bachelard’s thesis dives into the reciprocality of our impressions on a space, filling it with spirit and meaning, and the space’s impression on our imaginations, evoking what memory, energy, feeling has been put in. In simple terms, it is a reflection of the occupant’s soul. As such, Tee’s exhibition leans into the calm of her still life arrangements. Withdrawing from the busyness of everyday life, the space created by her art practice (and in the deliberate slowing down of making) becomes her refuge.

the house allows one to dream in peace resists the idea of homemaking and domesticity as practices that remain in the household. Traditionally feminine and confined to unwaged work, Tee’s methods and themes are often categorically relegated to craft. Homemaking is labour that is often unpaid and assigned to the woman. The inclusion of sewing and textile work in the art world are hard-won. Here, Tee pivots her usage of her textiles — an interest that has gone beyond her art practice and into dressmaking, among other things — and rather than creating a tableau that depicts a landscape (which is a traditionally more accepted form), zooms out and paints these soft sculptures as they are.

Through these paintings and soft sculptures, Tee shares her world, though in a way that allows a comfortable distance. Arranged across the floor are her textile creations: the subject of the paintings that surround the space. In the house, Tee seeks to find balance between participating in and retreating from life as we know it. Sewing is a naturally slow process, and these works are a disciplined and deliberate practice in mindfulness, and a retreat from the pursuit of immediacy as well as the impatience that pervades Tee’s life.

Bathed in neutrals — the colours Tee enjoys working with the most — the space is punctuated with pops of colour, likening them to wildflowers in a field. Wildflowers are a recurring motif in Tee’s work, recalling the signification of wildflowers as fleeting or fading away in the Bible. The impermanence of the wildflower is symbolic of the impermanence of man.

the house embodies her life’s paradox, juggling between the impatience to achieve things due to fleetingness of her time on earth and her tendency to withdraw from the active pursuit of life. And this is the space she has made to reflect that. This place is her living room, her gardenscape, her refuge and retreat. This place is yours, too.

— Carina Santos

GROUP SHOW

No City As Dear As

No place as dear as (Manila)... As the title prefaces, this exhibition is a recollection that pays homage to Manila, herein defined loosely as the greater Metro Manila area belonging within the National Capital Region. However, it is important to note that, in this instance, its relevance is not in its geographical boundaries nor in its historical significance, but in its function as a setting for the people that converge within it. This retrospection highlights the relation of how personal history and collective memory fuse in one city creating its unique identity.

There are a multitude of intertwining lives that move within the city: the residents who at one point of their lives called this place home, the regular visitors, the temporary guests, and the travellers who are just passing through. All of these lives intersect and interact to form permanent or transitory relations, each sharing their memories culminating to a montage of scenes/ scenarios from the most poignant to the most ordinary, meanwhile collecting stories and keepsakes that reminds one of how a place affects a person and how that person in turn affects the place.

As the city itself changes and deviates through the passing of time, so also comes the longing to reconnect and recollect. One tries to revisit a past, a place, a time, or a situation that one cannot truly return to — seeking to be re-introduced to a version of oneself that one has already left behind; re-familiarizing with relationships passed; or attempting to imbibe by proxy the experiences of people one has not met and are not likely to ever meet. All these are efforts to call back an echo of a time and a place that once was and may never be again.

In sifting through the memories and the moments, one may not always faithfully remember complete narratives or exact sequence of events, but what is often prominent is the sensory details like the sounds, the scents, the colors, the views, and the textures. They leave behind consequent feelings and distinct impressions that summon up the character of the place and the energies that surround it. Each fragment gives a layer to an intricate mosaic that is the image of the city.

Metro Manila is an amalgamation of unique stories and shared experiences. It is a latticework of contradictions and correlations, an unfolding tale of the people’s love-hate relationship with the city told against the backdrop of its complexities; the noise of cars and pedestrians, the palette of fumes that assault the nostrils, the bright displays in contrast to the grime of the buildings and streets, the constant humidity, and the sheer clutteredness of everything. It is convoluted and it is messy, but it is also vibrant and beautiful. It is often times perplexing but it is always dear.

- Arvi Fetalvero

VALERIE CHUA

Youth

From day one to death, life is often an exercise of remembrance.

Using oil paint to emulate the filter of a lens, the artist navigates ethereal composition of images. The figures move through stages of life, captured in play and pose: Eyes widen with lively imaginations. A tiny child learns how to fly through plane mobiles and hummingbirds, reaching toward a woozy tower. There is the sensation of long and languid summer holidays spent racing down muddy lanes. Memories arise of paddling in ponds and wading through lily pads, stockings jutting out like the witches of Oz. Other witches or warlocks are poised to kick off the ground. Groups of teenage friends move alongside each other to enter the unknown. Working folk push and pull at grand oceans and tall mountains. Until white-haired persons look out into the quiet, leaning back in dried-up lakes, and reaching upwards toward the sky.

As one does not always remember vividly, Chua continues her practice to acknowledge elements of life shown through a filtered lens. Despite frozen memories possessing a sense of the performative, the authenticity or value is never reduced. The core of her practice revolves around the appropriation of stock images, both from personal and public film footage. She explores the human inclination to curate, accumulate, and imitate in the multi-layered cultivation of "the self," now magnified in our contemporary era dominated by visual culture and social media. By employing images both familiar and universally recognized, Chua presents incisive observations of the world at large, emphasizing how the adaptable nature of aesthetics shape perception of ourselves.

In “Youth,” Valerie Chua creates images that show despite how every human may shift with age, there still pervades a sense of innocence.

Words by Lala Singian

GROUP SHOW

Totalidad

Marahang nabuo ang eksibit na Totalidad. Marahil dahil sa nagsimula ito bilang isang makasariling paghahanap ng materyal para sa pag-aaral ng sining at ekolohiya. O siguro sa sobrang lawak ng gusto nitong pagusapan naging mahirap na rin itong talakayin. Paano nga naman palalalimin ng isang eksibisyon ang dikotomiya ng kawalan ng espasyo at pagyabong ng materyal?

Pabulong ang ihip ng hanging nakikipaglaro sa mga puno at sumasayaw ang ilaw ng mga sasakyang nagmamadali sa patutunguhuan. Sa pagitan ng nagtataasang gusali, humawi ang mga ulap mula sa kakatapos lang na ulan, at nagsisimula pa lang ang gabi ngunit kitang-kita na ang liwanag ng buwan. Sa paglalakad sa siyudad, hindi maikakailang malayo sa pag-iisip ng ordinaryong tao ang sining. Ngunit, hindi maihihiwalay ang sining sa mundong pinalilibutan nito. Iilan lang ang makakaunawa kung gaano kadami, kalaki, at kalawak ang kalibutang punong-puno ng kagamitang sining. Papaano natin pinag-iisipan ang totalidad ng mga bagay-bagay na iniinugan natin? Sa likhang sining, papaano ipinapakita ng mga artist, sa maikling panahon, ang kalagayan ng kalikasan at ang kailangang gawin para mas marami pa ang makakakita nito? At dahil dito, kasama ang mga artists na sina Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, at Pope Bacay pinagninilayan at binibigyang-halaga ng Totalidad ang lawak at laki ng mundong pinalilibutan at kung paano natin ginagamit, sinasalba, at rinirisiklo ang mga materyal na nakapaloob dito. Sa eksibisyong ito, may pagkakataon ang bawat isang harapin ang kanya-kanyang mga proseso at buksan ang isipan ukol sa mga materyal na ginagamit sa bawat paggawa. Sa madaling salita, imbitasyon ang Totalidad magtanong ukol sa kaniya-kanyang praktis ng sining at pagnilayan kung ano ang ambag ng paggawa nito sa ating kalibutan.

Sa pagtuloy ng paglalakad sa pasikotsikot na kalsada at tumingala sa lawak ng kalawakan, pagkatapos makita ang mga ginagawang trabaho ng mga artist, hindi mawawala ang tanong na para saan at para kanino ba itong sining na ating dinadanas? Sa Totalidad, pinagsasama-sama ang mga obra nina Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, at Pope Bacay hindi para magbigay ng isang sagot pero bilang isang patuloy na imbitasyon na lumubog sa kasalukuyan at pagnilayan ang kabuuan ng ating pagmemeron.

Masisilayan sa video room ng Finale Art File ang eksibit na Totalidad nina Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, at Pope Bacay mula 27 ng Oktubre hanggang 24 ng Nobyembre 2023. (eyb)

______

The coming together of the exhibition Totalidad was slow yet deliberate. Perhaps, because it began as a way to study material for research on art and ecology or perhaps, due to the expanse of the concept, it became too complex to tackle. After all, how could one mere exhibition, in its most basic essence, deepen the nuances between the absence of space and proliferation of excess material?

The wind whispered, playing with the trees as lights danced around from cars rushing to their destinations. Between the skyscrapers, clouds cleared just as rain stopped and the moonshine peeked through the early night. Walking around the city, it is evident how contemporary art can feel so distant from the everyday and the quotidian. Yet, the practice of art, especially its materiality, belongs to the world. There are but a few of us who seek to understand the complexity of a world filled with materials. How could we think about the totality of everything that is around us? In art, how do artists present the intricacies and interrelations between life and our surroundings in their practices? And so, together with visual artists Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, and Pope Bacay, this exhibition contemplates on the vastness and depth of this world we live in and how one makes use of and recycles material. In this exhibition, there is space to deepen one’s understanding of material, how the process of making could be sustainable, and contemplate on how one’s practice belongs in the world.

As one continues through the winding streets, looking up at the expansive midnight sky, and seeing the works-in-progress for the exhibit, the question of art’s purpose in the world resurfaces. For what and for whom is the art that we experience? In this exhibit, the artworks by Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, and Pope Bacay are brought together not to serve as answers, but rather, as a continuous invitation to be present in the present and to consider the entirety of being.

View the Totalidad exhibition with works by Audrey Lukban, E.S.L. Chen, Faye Abantao, Jel Suarez, Jezzel Wee, Noelle Varela, and Pope Bacay in the Finale Art File video room from 27 October to 24 November 2023. (eyb)

ANNIE CABIGTING

When we look at art...

A step back. A tilt of the head. A bag strap slides off a shoulder, and the weight shifts slightly as it’s adjusted. Hands reach out for each other from behind, posture is straightened, a head leans forward. Hushed conversation, a cell phone is taken out to check a text, snap a picture, and air rushes out of a seat cushion as the weight of a long day at the museum presses into it. The act of looking at an artwork is as much a physical exercise as it is a mental one, and this dance in all its infinite variations between artwork and viewer is performed in thousands of museums and galleries everyday.

This relationship that people have with art – how they behave around it, how they experience it, how they look at it, and, most importantly, how they look when they look at it – has occupied a space in Annie Cabigting’s mind throughout her career.

These paintings always begin with a photo. Some are taken by friends, and Annie may come across them on social media and ask for permission to paint it. Some keep their eyes peeled for interesting figures and paintings, and then send them to her to see what she could make out of it, and some others, she has personally taken herself.

Beyond slight tweaks for composition, she then paints these photos in a photorealistic style almost exactly as how they were. These paintings, however, aren’t solely about the artworks Annie has meticulously reproduced, or the galleries that they inhabit: they are, foremost, about the people looking at these paintings and walking around in these galleries.

Like making a new friend, one would need to spend time with an artwork before it begins to reveal itself. Frozen in time as they step back, tilt their heads, adjust their bags, and lean forward, the people in Annie’s paintings have an eternity to acquaint themselves with what they’re looking at.

Though an eternity is out of reach, there is a moment right here – after all, you are here with them. They are here with you.

CHRISTMAS GROUP SHOW